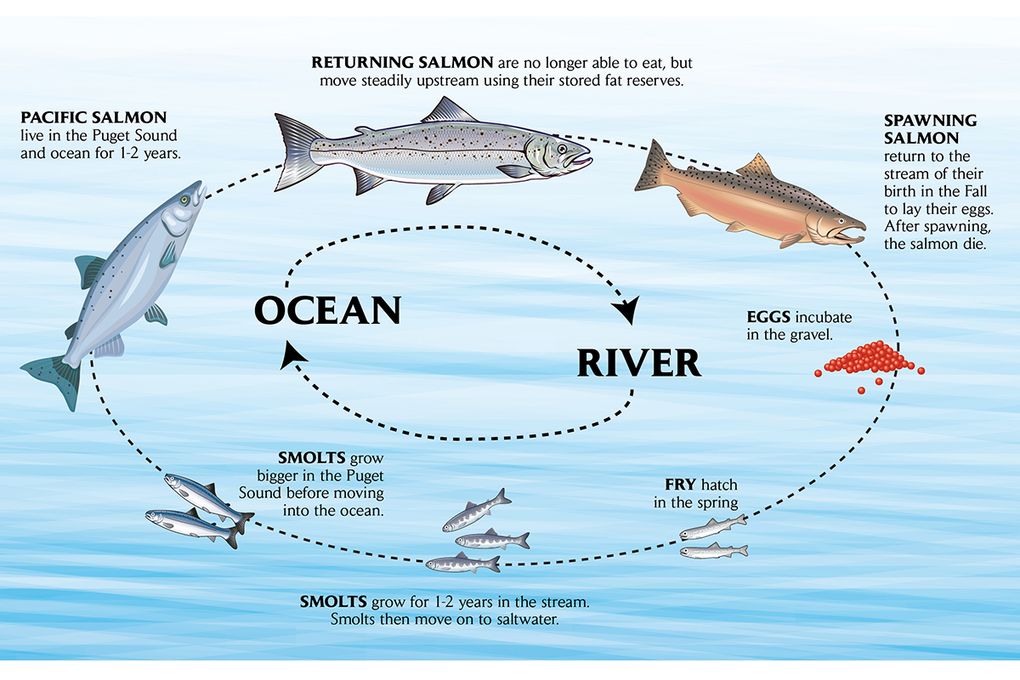

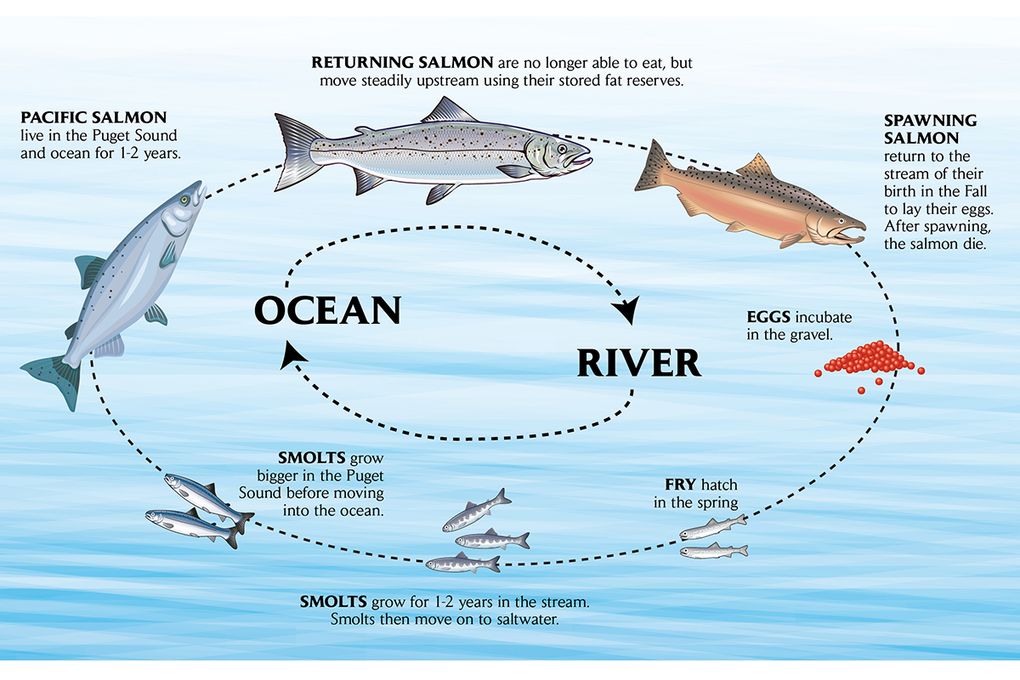

The life cycle for salmon begins in freshwater, when a redd, or female's nest of eggs is fertilized by the male salmon. These eggs remain in the gravel throughout the winter as the embryos develop. Cold, clean water is essential for healthy growth and survival of the egg. Water flowing through the gravel delivers oxygen to developing eggs. In the spring, the eggs hatch and alevins emerge. Alevins stay close to the redd for a few months. Once they have grown in size and consumed the yolk sac attached to their stomachs, they emerge from and gravel and are now considered fry. The fry swim to the surface of the water and begin to feed. The survival of fry is dependent on the quality of the stream habitat which they are in. Boulders, logs, shade, and access to side channels are important in allowing fry to hide from predators and prevent them from getting flushed downstream during floods. When the fry are one inch long, they are called fingerlings. The tiny fingerlings grow in backwaters and stream margins. As the fingerlings grow, they move to the main channel. Carried downstream by the spring thaw, salmon begin the amazing changes called smolting. Smolting is triggered mainly by the increasing daylight hours and rising water temperatures of spring. Individual territorial behavior gives way to more cooperative schooling behavior, gravel colored markings change to a silvery hue, internal changing mostly affecting the kidneys allow for the transition from fresh to saltwater. Estuaries provide a mix of fresh and saltwater habitats in which salmon smolts prepare for entering the ocean. Swimming with the tide, young salmon leave their home rivers, moving around the pacific ocean in varying migratory patterns, they live in the ocean for anywhere from 2-5 years, growing and maturing. Ocean life means escaping predators as well as avoiding fisherman. To preserve the dwelling fish runs, fishing limits are set on all takings of salmon. Researchers have found that while in the ocean, salmon often travel phenomenal distances for food. During this time, they increase in weight--often more than 100 fold. Temperature and food conditions can be highly variable from year to year. A large percentage of fish do not survive the difficult ocean passage. Eventually an instinctive trigger tells mature salmon the time has come to return to their home streams and reproduce. Triggered by an irresistible instinct to spawn, salmon find their way back to the river mouth, then head upstream with great determination. While dams block their way, many have fish ladders that allow fish to swim around the dams. The homeward bound salmon no longer eat, living off of stored fat, pausing only occasionally to rest. They endure weeks of struggle against powerful currents up hundreds of miles of river. Bruised and battered, wearing tooth marks from unsuccessful predators, they swim on to the headwaters, their health declining rapidly. Even after spawning, the cycle is not quite complete. Salmon carcasses give food to the forests, the predators, and the insects.

In 2001, the population of coho in the Russian River was down to less than 100 fish--potentially down to a population of around 10. Stream flows are elevated to around 7 times above the natural flow level on the Russian River. We can't reduce the flows because of the demand for water, but we can spread the flows to reduce the velocities. One method of doing this is creating channels for the fish where the waters will not move at such a high velocity. This creates the ideal rearing habitat for coho salmon. When there are winter floods and the flow goes up and the fish need to get out of the way of the high water, they can go into channels that are built. With small tags plants in juvenile fish, you can use antennas to detect when the fish enter the habitat features so you can know when the fish are coming and going from the habitat features. Fish stay in these habitats during high flood events for up to a week at a time.

No comments:

Post a Comment